Yield farming protocols are primarily based on fees generated by providing liquidity on automated Market Makers (AMM) like Uniswap. Typically, a pair like ETH/USDC is siloed into a 'pool,' and the liquidity provider (LP) is exposed only to that pool. The additional yield comes from staking, which involves getting tokens for locking funds in a dapp or blockchain. These are the primary sources for the absurd Annual Percent Yields (APYs) promoted by everyone from Gemini to your typical crypto influencer.

Anyone with some grey hair will immediately see this as impossible, like someone telling you how they created a perpetual motion machine. If someone truly found a 100%+ return strategy, they would not be telling everyone because that would dilute the rare opportunity. For example, in the early 2000s, a retired Michigan couple figured out how to make 80% returns off a new, poorly conceived lottery. He netted about $8 million over almost a decade and invited close friends and family. They did not advertise for investors on Facebook.

I will not discuss the staking returns other than to note that the best-case scenario here is to earn 10%. Like all good scams, there is a valid case for the strategy (staking on Ethereum offers 4% APY, and performs a real service). However, most staking schemes have no purpose other than the classic Ponzi game. The promoter gets early investors to stake in their PonziToken. Their over-the-top online game, which often explicitly uses the word ‘pump,’ motivates more noobs to buy the PonziToken for staking, allowing the scammer to pay off initial stakers by minting new tokens that have increased in value. It's such a stupid strategy I have no interest discussing it in more detail.

Examining the LP strategy, I will focus on Uniswap because it is the least scammy and has the most value locked in AMM pools. I will also focus on the ETH/USDC pair to make the application less abstract (it's hard to keep track of tokenA and tokenB). An LP provides an option to traders: you can buy ETH for $1100 or sell it for $1100.1 Options have value, so traders pay for this value via a fee of 0.05% or 0.3% of the value traded. LP profit equals revenue minus expense.

The main problem in AMMs is that LPs are either wholly ignorant or do not appreciate the value of the option they are writing. Note the allusion to 'impermanent loss' as if it is not real. To see the flaw in this thinking, consider the strategy of writing (selling) calls while long a stock. Such a strategy adds yield to the writer when the options are sold. If the price of the stock goes up, this covered-call position makes money, just less than if he didn't write the call; if the stock price stays constant, the writer makes a positive amount due to the call premium; if the stock price falls, the writer loses less than he would have without selling the worthless call. A smooth-talking salesman could sell this investment as costless because, as framed, in no scenario does the covered call writer lose money (this site by Ribbon finance is bold enough to post its crypto option premiums as APY).

The key to seeing the flaw in this accounting is evaluating the portfolio's constituents. Arbitrage pricing theory, and common sense, tell us that the pieces of a portfolio add up to the entire portfolio's value. If that were not true, one could buy a portfolio, sell its components, or vice versa, and make a profit. In the case of the covered call, you can evaluate the stock and call position separately and note that the value of the call, absent mispricing, is equal to its expected value. The same is true for an LP position: it generates fees but pays via the expected value of the impermanent loss. Considering the LPs are generally unaware of this option, and LP promoters do not try to estimate this expense, it’s easy to see why LPs are massively undervaluing the option they are writing.

The neglect of this cost is everywhere. For example, here is a list of top yield farming opportunities, and they promote Uniswap as generating a nice 40% APY.

How do they get 20-40%? By annualizing the fees generated divided by the Total Value Invested in the pool. If you look at the prominent Uniswap ETH/USDC pools in that way, they generate APYs of that magnitude. This is generally willful ignorance.

Uniswap LPs generally lose a lot of money when the costs of the options they write are calculated. It is an unavoidable cost [I wrote about this here]. If you do not understand that you should not be providing liquidity pools because you are being taken advantage of; if you do understand that you should not be providing liquidity to AMM pools because you know you are losing money.

Arbitrage Trading LP Revenue Is Insufficient

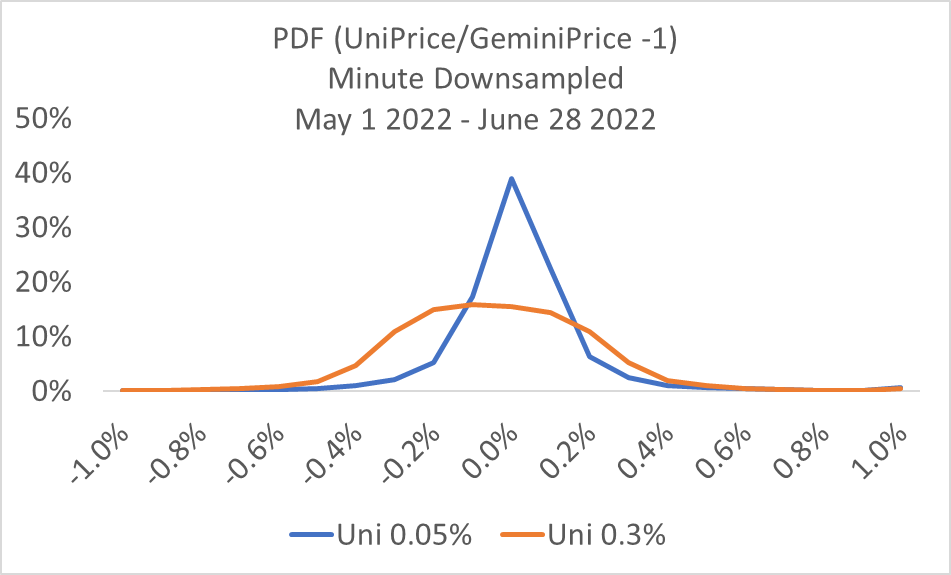

Arbitrage trading will not solve the AMM problem, regardless of the fee. For most active markets, the Uniswap pools are pretty efficient in closely following the prices on centralized exchanges such as Binance, Gemini, and FTX. For the past few years, centralized exchange prices have been within a 0.1% of each other at all times, so we can use one as a reflection of the 'true' price. Consider the PDF below showing the distribution of the pricing difference between the Uniswap pools and the Gemini price, using downsampled minute data from the past couple of months.

If AMMs have prices closely linked to the 'true' price one sees on major exchanges, it is tempting to download centralized price data to see what this implies for a new AMM.

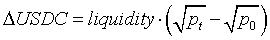

For constant Function Market Makers (CFMMs), The AMM math implies the following relation between a pool's liquidity and the price movements. The tricky thing to note here is that the change in the square root of prices directly relates to the USD traded.

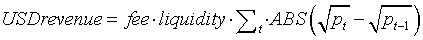

To estimate revenue for LPs, one multiplies by a simple fixed percent fee (e.g., 0.05%, 0.3%) [we will ignore the fact that the fee is applied to both tokens and just focus on the USD revenue. As an approximation, it is sufficient]

Given this formula, it can appear we can estimate an LP's revenue by looking at the change in prices taken from Binance or Gemini. Note liquidity is a proportional term, so we can look at the total liquidity of the pool or apply this to a potential investment and it works the same. There is no distinction between a marginal LP and an initial LP. In either case, we multiply by the fee to get the LP revenue.2

If we apply Gemini's price data by minute using this method, such an approach will dramatically overestimate AMM pool arbitrage volume. If the current price on an AMM pool is 0.5% away from the price on Binance, and the fee was 1.0%, this would not be attractive to an arbitrageur interested in making profits. No profit-maximizing arbitrageur would pay 1.0% to earn 0.5%. We see this in the Gemini-Uniswap pricing difference graph above, where the 0.3%-pool has a fatter distribution than the 0.05% fee pool.

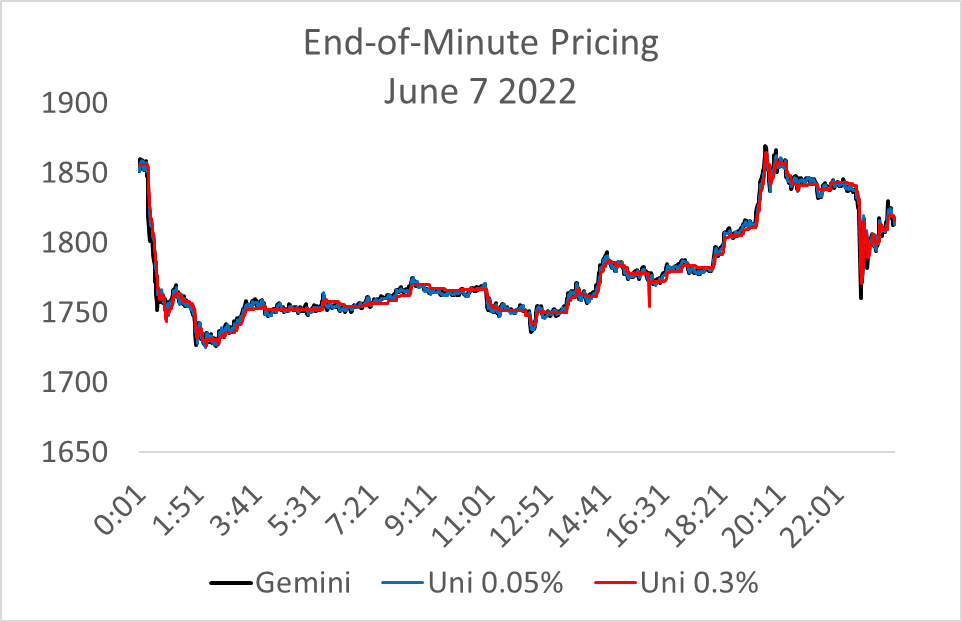

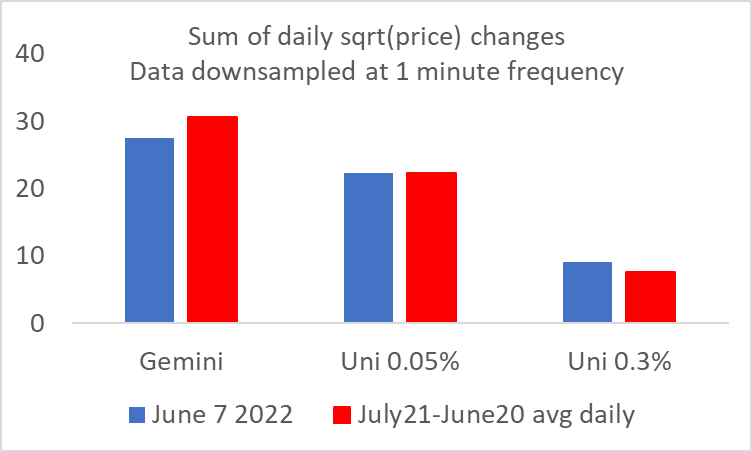

The fee impacts the total sqrt(p) movement straightforwardly. Consider the mathematical curiosity of the infinite coastline shown above. If we assume coastlines are fractals, then the coastline looks the same in every dimension. With infinite precision, we should say that the coastline of California is as extensive as that of the city of San Francisco. While this is an absurd limit constrained by the Plank length in the real world, it highlights a profound point: the sum of square-root-of-price changes is a function of the precision of any squiggly path we are looking at. Below is a chart of intraday prices, down sampled to the minute, on a particular day this month. Here is the Gemini, Uniswap's ETH/USDC 0.3% fee pool, and their 0.05% fee pool, down sampled to the minute.

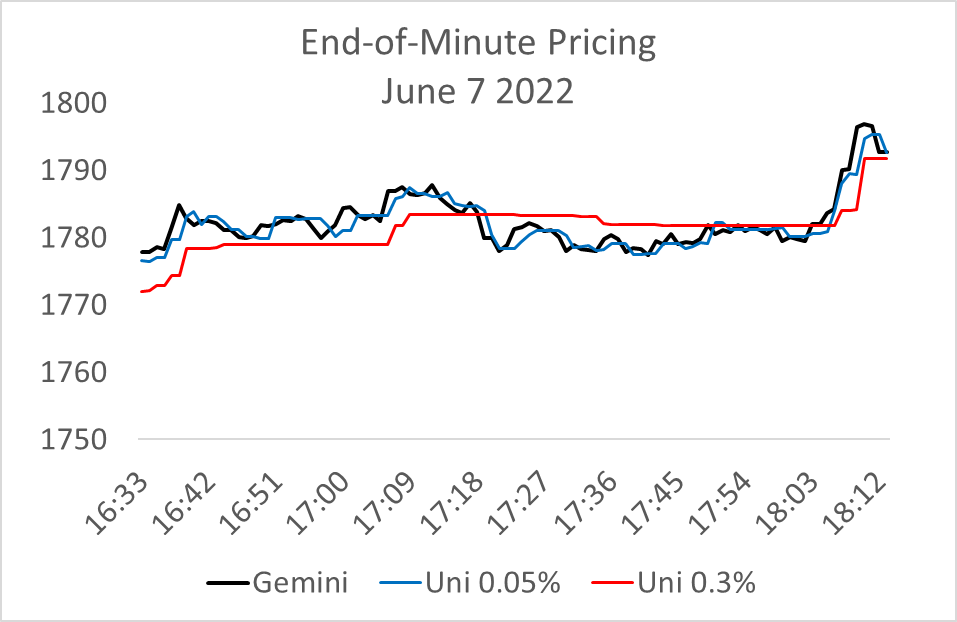

The lines are basically on top of each other. However, looking more closely, we can see how the larger fees reduce the sum of all those price changes. Below is a picture of a 2-hour window; we can see clearly that the 0.3% pool shows much more price stasis.

While it is not obvious, the 0.05% pool also fluctuated less than the Gemini price. While this day looks rather unusual, it represents the past 12 months' worth of data. The chart below shows that the 0.05% fee pool had about 75% of the square-root-price changes, while for the 0.3% pool, it was only 25% of the Gemini price changes. If you create a simulation where you change prices only when they move more than 0.05%, or 0.3%, from an initial price, you will see a similar pattern. There is no getting around it.

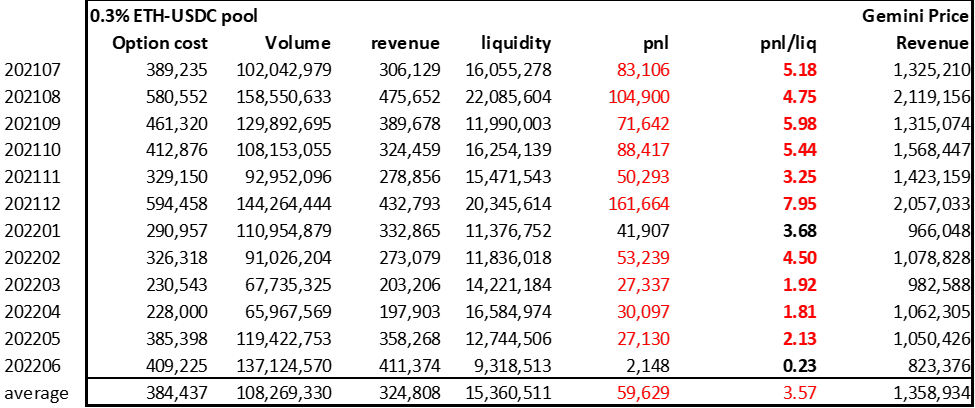

Currently, Uniswap LPs in both of these pools lose money when we apply the standard option cost. To figure this out, instead of looking at each LP and seeing whether they made money unhedged, I assume they hedged their books perfectly as good capital stewards do. This involves multiplying the gamma, which is unambiguous, and the price volatility that day. Since gamma is a function of the liquidity and price, and these two pools refer to the same asset, they have the same price. So let us look at the pnl/liquidity in the two pools. [I explain this in more detail here].

Uniswap Pool Data

Here we see the 0.05% pool loses about twice as much as the 0.3% pool when LP positions are normalized by units of liquidity.3 Currently, the 0.3% pool is the lesser of two evils, the winner of the least ugly pig contest.

However, the 0.3% pool actual revenue is only 20% of that implied by Gemini minute-down sampled prices. If you anticipated the revenue from arbitrage trading via Gemini minute data, you would have been off by a factor of 5. This is explainable given arbitrageurs need the pool prices to deviate by 0.3% from the Gemini price before becoming profitable; arbitrageurs ignore all moves within this range.

In contrast, the 0.05% pool generates slightly more revenue than if it matched the Gemini minute price data. If we consider that the Gemini pricing data will overstate the arbitrage price changes due to the 0.05% fee, this implies the appearance of liquidity traders, who appear absent on the Uniswap 0.3% pool.4 Casual traders prefer the more liquid and cheaper ETH/USDC pool. Indeed, it would be absurd for it to be any different.

While the 0.3% pool may be less unattractive than the 0.05% pool currently, at least the 0.05% pool has a chance. The net profit for an LP providing liquidity only to arbitrageurs is at best zero. This is obvious when you consider that the arbitrageur is taking the other side, and they have the option to initiate action. Their net pnl includes not just the fee on the AMM but the transaction costs paid to hedge on centralized exchanges or pay gas.

The good news is that there are signs of life in the 0.05% pool, the appearance of some liquidity traders. The bad news is few are focusing on the essential issues. Many in this space do not realize 1) AMM pools are broken and 2) the solution involves creating a way for LPs to make money without going to pseudo-decentralized, censorship/confiscation-tolerant, low-latency blockchains (e.g., Solana, whatever dydx is planning).

The Needed Solution

A standard central limit order book has three types of traders: uninformed, informed, and market makers. The informed traders invest in data, models, and hardware to identify temporary mispricings. The uninformed are ignorant for rational and irrational reasons: they want to buy a car (liquidity traders) or are delusional and trading on irrelevant information (noise traders). As informed and uninformed traders do not show up simultaneously, market makers arise to provide liquidity continually by posting resting limit orders to buy and sell.

In equilibrium, all groups generate benefits equal to their costs. The informed trader's costs are balanced by revenue from adversely selecting stale market maker limit orders. The uninformed pay the market maker by crossing the spread, benefiting from convenient, quick trading. Market makers post knowing they will trade with both types of traders, setting limit orders such that the revenue from uninformed balances that they lose to the informed. Given the changes in information and technology, the equilibrium solution is different and has changed rapidly over the past 40 years.

Historically, market makers dealt with this problem via a state-imposed monopoly. For example, for decades, one could only trade certain stocks on the New York Stock Exchange, and a specialist would process the orders. While competition arose in the 1970s, as late as 2000, most specialists would lose money 'trading' only a handful of days a year.5 This is still a dominant solution, in that the 2008 financial crisis created new power for US regulators to shut down over-the-counter markets using the standard rationale of ensuring the safety of our economic system. This helped venues like the CBOT and CME in Chicago tighten their control on futures and derivatives.

As the internet developed, electronic market makers like Archapalego and Island changed the equity trading game. Like Uber, they became too big before US regulators could figure out how to attack them, and forever changed asset trading. Yet these new electronic market makers had to create some way of generating an advantage, a barrier to entry.

They compete mainly by developing economies of scale in hedging and raw computer hardware, in combination with some alpha, to give them a bleeding-edge advantage. The key is to be five milliseconds faster than the next guy because if you see a 'true' price change coming, you want to lift your limit order and let someone else get run over; if you know the price is going up, you want to post your bid at the new higher level the top of the queue. Given the price-time nature of limit order books, the value of being n-th fastest declines rapidly.

The latency game is all about avoiding adverse selection. Market makers will not be those who create price movements; that's a different set of skills and focus. They just need to be quicker at sensing such price movements. High-frequency trading shops get a bad rap, but the net effect has been a dramatic reduction in equity trading costs since 2000. It's strange to see leftists pining for the good old days when monopolists would post bid-ask spreads of 1/4 in Microsoft, one of the most popular stocks; today, highly liquid stocks are often only a penny spread. Competition is messy, and the winners are not vetted by a Star Chamber. The pleasant demeanor of your average crony-capitalist hides inefficiency, promotes stasis, and worse, encourages people to lie (they want their privileges, but always present it as mitigating systemic risk).

Another active focus for high-frequency market makers is identifying the liquidity traders from the informed traders. Retail flow from places like RobinHood or ETrade is known to be uninformed.6 There are many mechanisms to identify this flow, and they are often pursued via a complementary service, or sold to the highest bidder (the savings are passed on via competition).

The AMM is a great innovation but has not yet solved the problem of generating a sustainable automated exchange. It's on borrowed time because the initial excitement created by the success of SushiSwap tokens and then Uniswap's airdrop masked the overall poor performance for LPs. Lately, dydx and perp.fi generated large trade volume primarily by users gaming their reward system.7

Almost all of AMM volume is a mirage, arbitrageurs making money off of LPs too stupid to understand the cost of the option they are writing.8 These LPs see the fees but neglect to quantify the 'impermanent loss.' Such losses can be ignored in a big bull market like 2021.

What DeFi needs are solutions that allow LPs to distinguish between themselves. If all suppliers have the exact same cost and quality, as idealized by many, it would not be a utopia; it would be unsustainable. The profit on such a product or service would be driven to zero, and the market would collapse: suppliers need to make a profit in a sustainable market, and buyers need to collect consumer surplus. LPs need a mechanism for building barriers to entry while still obeying Satoshi’s principles: permissionless access, censorship resistance, immutability, and transparency.

There is market impact, but that's a distraction here

Restricted ranges, Uniswap v3, don’t change anything about the profitability of these pools. It merely changes the capital efficiency relative to a v2 if you manage it correctly. Many LPs do not monitor their ranges, however, so net net, has had an ambiguous effect on the average LP. For example, if you have had an inactive range on Uniswap for the past month, that is worse than supplying liquidity for an absurdly large price range. More importantly, the gamma generated by v3’s liquidity, and volume on those pools, is sufficient to assess their profitability. One does not need to isolate all of the ranges and evaluate them. To the extent a range is inactive, it will not be reflected in the liquidity numbers; it will not partake in revenue, or experience the losses intrinsic to providing liquidity (ie, gamma). A v3 position has a delta, but that is not a cost because it is avoidable, in that it can be hedged away without cost.

It’s better to use gamma when comparing option values, but here the gamma is simply a function of the same ETH price for both, so comparing liquidity generates the same result as comparing gamma. As most readers do not intuit gamma easily, it is better to avoid it when possible.

Applied to 1-minute data, the 0.05% bound would reduce the square root of price change sums by 10%.

Invariably, market makers with privileged access to flow would present themselves as if they were speculators. Their consistent profitability showed this was not remotely true.

When high-frequency traders pay for this flow many see this as a malicious conspiracy, but it is part of a process that has reduced spreads by a factor of 10. Not only is grandma’’s spread tighter, but the HFTs also are not going to flinch when she makes a fat-finger trading error and buys 10x more than intended: a big order from the uninformed will have a lower trade impact.

The dydx CEO Antonio Juliano went on Bankless while this absurdity was happening, and the interviewers were clueless as to what was going on, and just asked the CEO how it feels to create such a popular exchange; these guys had no idea what all that volume represented. It was fake volume generated to get rewards, which were valuable because people looked at the raw volume numbers and mistakenly thought that represented ‘real’ volume. A complete clusterpuck, so typical to DeFi. See this twitter thread.

I have heard several people, such as Dan Robinson of Paradigm, say that given the depth of the AMMs on Uniswap, who is to say that the ‘true’ price is on Binance as opposed to Uniswap? This rarely gets any pushback but is wrong for several reasons, and I’ll mention two.

First, on centralized exchanges, latency is in milliseconds, while for trustless blockchains, it is at least several seconds. If you know where ETH price is going, you are not going to first leak it to a blockchain that will sit on that info for 10 seconds; you will go to the low latency venues first. Uniswap is still reacting, not setting prices.

Secondly, an AMM uses a math formula that is static for 10 seconds at least, while a centralized limit order book contains several well-capitalized high-frequency traders employing algorithms that respond to trades within 20 milliseconds. The static level-2 quotes—depth of book—generates an apples-and-oranges comparison. Not only are there often limit orders explicitly hidden on many exchanges, but there are also many more limit orders implicit in dynamic strategies coded into servers colocated with the exchange.

No comments:

Post a Comment